For birders who find it hard to get worked up about sparrows, the Lark Sparrow may be the perfect ‘gateway drug’ to get them hooked. Certainly these birds are anything but “little brown jobs," with their boldly-patterned plumage.

But looking (and listening) deeper, we find them unique among the sparrows in other ways. Firstly, Lark Sparrows are in their own genus (Chondestes.) Also, while most sparrows get right down to the business of copulation with little fanfare, Lark Sparrows engage in the most elaborate and extended courtship displays of any member of the family. The male dances about doing what Martin and Parrish (Birds of North America species account) describe as a ‘turkey walk’ for five minutes or more, strutting and flashing the white tips of his tail at the female. Before mating takes place, he picks up a twig, which he gently passes to the female as they copulate. Now, that certainly passes for high romance in the bird world!

Equally distinct is the highly organized and exceedingly complex song. Most sparrows get by with a very simple repertoire of one to a few different song types. The Lark Sparrow repertoire may be the largest of any sparrow.

Richard Hedley and I recently published an analysis of the Lark Sparrow song, Structure of Lark Sparrow Song in California, and found that it is structured following a fairly strict set of rules, gaining complexity using four levels (hierarchies, if you will) of variation. The series of videos below will demonstrate what we mean.

FIRST, we need a common vocabulary for describing the parts of a Lark Sparrow song. They typically give a short (4-5 second) burst of song, followed by several seconds of silence before the next burst. We used the term "strophe" for each burst of song (for reasons explained in the paper...) and found that each strophe contains a set of individual elements, grouped into short syllables as shown in the example below:

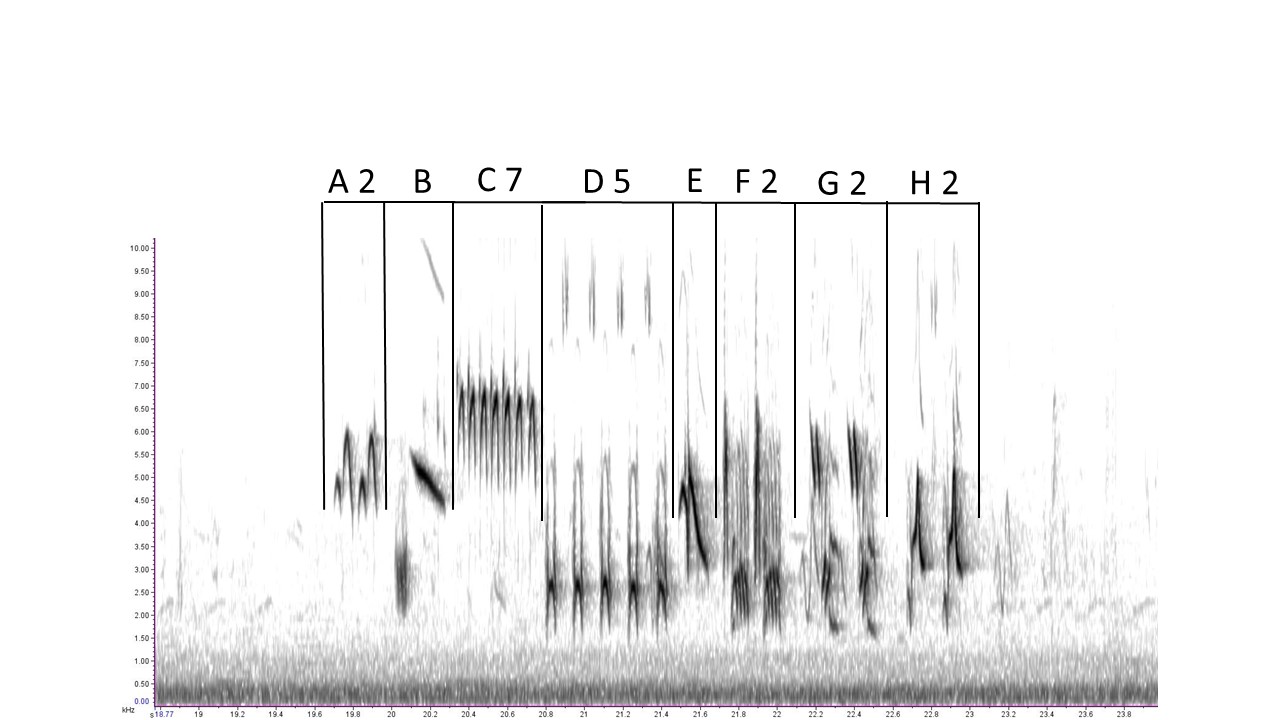

We can then identify each unique element with a letter of the alphabet and add a number to indicate how many times an element is repeated within a syllable. Clear as mud? The example below using the same strophe as above should help. Here each syllable has been labeled based on the element used and the number of repetitions.

So now we can see and hear how a typical Lark Sparrow builds up a truly remarkable repertoire using this structure. Below a typical strophe from a bird I recorded near Sacramento, California:

Spectrogram recorded and produced by Ed Pandolfino

This first strophe uses just four elements (A, B, C, and D).

Spectrogram recorded and produced by Ed Pandolfino

The very next strophe from this bird introduces some new elements (E, F, and G):

Spectrogram recorded and produced by Ed Pandolfino

The next strophe introduces three more new elements (H, I, and J):

Spectrogram recorded and produced by Ed Pandolfino

A Lark Sparrow will continue in this manner typically using 10-15 different elements, varying the order of elements AND the number of elements within syllables.

But wait, there’s MORE... Most Lark Sparrows, if one records long enough, will suddenly switch to a completely different set of elements (a new “theme”) and use these new elements to structure subsequent strophes. In this case, after several strophes using elements A through J, the bird suddenly switched to a new set of elements:

Spectrogram recorded and produced by Ed Pandolfino

The table to the right shows the pattern from a different Lark Sparrow I recorded (in Calaveras County, CA) switching from the first theme to a second and then back again. We found some birds using as many as three different themes. The most remarkable observation of all was that birds almost NEVER mixed elements from one theme into a different theme. There are “rules” here, and there must be some good reason that any self-respecting Lark Sparrow is bound to abide by them.

One can imagine that by using four levels of structure variation (distinct elements, different orders of those elements, different numbers of an element repeated within a syllable, AND different themes), a Lark Sparrow can produce astounding variety in the course of each performance.

Ed Pandolfino is a member of IBP's Board. He earned a Ph.D. in Biochemistry from Washington State University. After twenty years working in various management positions in the medical device industry, he retired in 1999 and has since devoted his time to ornithology. Ed has served as president of Western Field Ornithologists, vice-president of San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory, conservation chair for Sierra Foothills Audubon Society, and Regional Editor for Northern California for North American Birds. He has published more than three dozen articles on status, distribution, behavior of western birds. He co-authored with Ted Beedy, Birds of the Sierra Nevada: Their Natural History, Status, and Distribution published by U.C. Press in May 2013. He has conducted ornithological field research and consulted for the US Forest Service, The Nature Conservancy, Point Blue, Sacramento Valley Conservancy, and Williams Wildland Consulting.