For almost 2 years, IBP scientists have had the pleasure of collaborating with a man of many talents, software developer Joe Weiss. In late 2022, IBP Acoustic Avian Biologist Jerry Cole needed to scale up our audio processing capacity and knew that cloud computing would be a good option.

“At the time I had some tools that I had built, but it wasn't a unified system, which is what I wanted. However, there weren't any prebuilt options to run BirdNET (Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s research platform for detecting and classifying avian sounds using machine learning) on the cloud,” says Cole. “Through some poking around I discovered birdnetlib, written by Joe, which simplifies a bunch of BirdNET operations in Python, and thought I'd see if he would be interested in building a web interface for processing our audio. Luckily Joe was excited to build that tool! In addition, he wanted to make what he's building open-source so that others will be able plug into this framework and get going.”

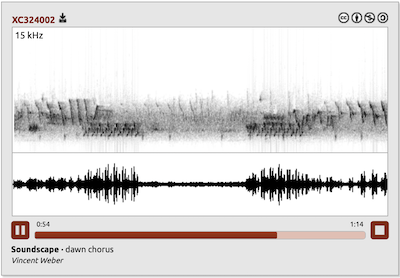

A spectrograph of an audio recording of just over one minute of the dawn birdsong chorus on the coastal plain of North Carolina. Autonomous audio recordings contain huge volumes of data and AI tools like BirdNET can help scientists pick out the sounds they are interested in. Recording by Vincent Weber/xeno-canto.org.

And so “AudioDash” was born. AudioDash is a cloud-hosted system that users interact with in a web browser. It can classify bird species within large amounts of audio data, organize and store those results, and provide an interface for reviewing particular subsets of identified recordings. AudioDash has helped IBP expand our bioacoustic work significantly- we now have about a dozen projects using audio data. “There is no way that we could handle our current volume of project audio without a system like AudioDash,” says Cole. “It's been a pleasure working with Joe on creating and expanding AudioDash- an added benefit is that Joe is excited about the birds we're trying to detect!”

Joe was so great to work with on AudioDash, we quickly talked him into another project: MAPSNet! MAPSNet is a software application that will make it easier for MAPS operators to submit their bird banding data while streamlining the extensive data verification process we use to ensure that the data are as close as possible to error-free and are ready for mark-recapture analysis.

Joe agreed to a brief interview so we can introduce the talented guy who has helped IBP elevate our work in the last couple of years. Thanks Joe!

Where do you live?

I live in Greenville, N.C., about an hour from the Atlantic Ocean. I grew up on the ocean; a lot of my family members were commercial fishermen.

How do you describe your occupation?

I think of myself as a software developer who works mostly with sound and data. I work under the umbrella of my small consulting company, Tungite Labs. I split my time between working for a handful of regular clients, developing new open source software libraries, and maintaining an old (at least in internet years) multimedia publishing application called Soundslides. Soundslides will be 20 years old this coming year, and it’s on a long, slow path to obsolescence, but I can’t walk away from its small but enthusiastic customer base.

A Mississippi Kite catches a large beetle in mid-air. Photo by Donald Edward Odom Jr.

How did you get involved with IBP?

When the pandemic lockdown started, I had a bit of free time, and I wanted to build a device that would alert me if a Mississippi Kite (spark bird!) was calling nearby. So I wrote a Python library for Cornell’s BirdNET model and used the new library as part of a system to monitor our yard. To this day, my wife Stacy and I still get a text whenever a MIKI is vocalizing near the house. I published the Python library as open-source on GitHub, and IBP’s Jerry Cole reached out to discuss using the library to analyze large collections of audio data. That collaboration with Jerry evolved into a software system named AudioDash, which helps IBP’s acoustics team do their work.

Were you interested in birds before getting involved with IBP?

Absolutely! I was into birding, but the work with IBP has been miles beyond where I thought I’d go with birds. Now I band birds at a banding station once a month, regularly deploy my own set of ARUs, and generally think about the intersection of software and birds all the time.

You even took one of our bird banding training classes! How was that?

I attended the Beginning Bird Banding workshop this past June with IBP’s MAPS Coordinator, Dani Kaschube, at Wolf Ridge Environmental Learning Center in Minnesota. As part of the MAPSNet project, I needed to better understand the data on a MAPS data sheet, especially when implementing the many existing validation routines for the new system.

BP, CP, HA, HS, etc.—before the class, I saw these as just variables in a Python object to be populated, formatted and verified. Now, I see more of the bird that those variables represent.

Joe examines a thrush at the Beginning Banding Workshop taught by IBP's MAPS Program Coordinator Dani Kaschube last summer. Photo courtesy of Joe Weiss.

The class was incredible. Dani broke everything down in a way that even a complete beginner like me could understand. Before this, I had never held a bird in hand. Next thing I knew, I was blowing all over an Ovenbird looking for molt and checking out its brood patch.

After getting back home after the class, I have been able to continue banding one weekend a month with a project in North Carolina. I still have a lot to learn, but it’s been an amazing experience, and the MAPSNet verifications now make so much more sense. I think the best software is created by people who actually use it, and I’m lucky to count myself as a bander now.

How do you like working with IBP?

I absolutely love creating software and learning about birds, so working with IBP hits all my bliss points. From a pure geek wow-factor, the cloud-based system we’re building out for AudioDash is a bit of a marvel. It's incredible to see what can be achieved with sound and machine learning, especially as the field continues to grow and evolve at an astonishing pace.

Also, the people I work with are truly delightful! For most of 2024, I've been meeting regularly with IBP Biologists Dani Kaschube and Emma Cox, and a few months ago, Lauren Helton began joining us as well. I've greatly appreciated their patience and generosity as they've guided me through my learning curve with MAPS and the Pyle guide data. I've learned so much from them.

Have you always worked in software development?

Software development is actually my second career. I was previously a photojournalist and editor, working on staff for MSNBC and McClatchy Newspapers. I’ve had assignments all over the U.S., Mexico, Nicaragua and Peru.

I’ve worked with all kinds of data as a software developer since I left journalism in 2006. Some of that data has been financial or textual, but there’s been a lot of audio, video and image data as well. The work with IBP is the first time I’ve worked with natural sciences data. I've worked as a developer, manager, and CTO with start-ups, but I enjoy working with smaller organizations in a developer role—it’s where I find the most fulfillment and excitement in my work.

I’ve enjoyed the diversity of my client work, shifting domains from accounting data and analytics to creating design and video production software. Now I’m happily bird-focused. A year ago I handed off all my non-bird related clients and I’ve been able to work exclusively on bird-focused software development. Not all of the work is public yet; it takes time to develop and document open source software.

What do you like to do when you’re not performing software wizardry?

Birds used to be my hobby, but now they're apparently a load-bearing component of my personality. I also play several musical instruments and enjoy learning new ones. I play the ukulele most often, largely because it’s convenient—I have them scattered throughout our home. I also enjoy making field recordings of quiet places. My favorite recording is from the Quinault Rain Forest on the Olympic Peninsula.

Stacy and I share a love for camping and hiking, and we travel as often as our schedules allow. She also took Dani’s class in Minnesota in June, and is banding here in N.C. as well.

Any regrets now that we have sucked you into working with birds and bird data?

Only that I wish I would have started doing this sooner. It feels surreal to be able to combine two passions into meaningful work. I feel guilty at times.