By Lauren Helton

Our first season on Rota wrapped up on May 30, and after a summer of work on the mainland, I’m back on Rota preparing for our second round, which is certain to bring new discoveries and challenges.

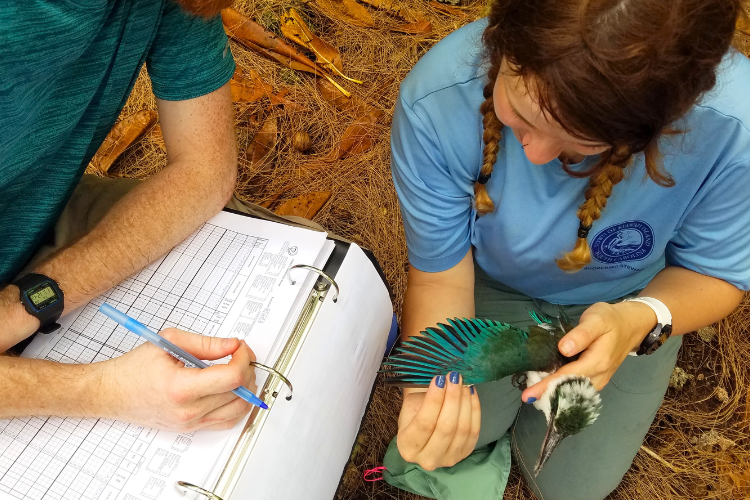

Axel holds a sihek (Mariana Kingfisher) wing open so that the coloration can be photographed. Photo by Kristin Attinger.

Firstly, I want to extend my enormous thanks to technicians Kristin Attinger and Axel Rutter for all their hard work in that first ever banding season! Being the first crew on a pilot project, having to forge ahead with work on a remote island in a different culture from your own, and working on species with little or sometimes no prior documentation, is no easy feat! It's a huge credit to those two that our first season wrapped up extremely successfully and smoothly. I couldn't have asked for a better pair of bird banders to begin this project with!

Let me recap how the season went: While I was out there for the month of March, the three of us established six new banding stations around the island's various habitats, and began to catch birds. I left at the end of March to get ready to prep my next field crew, the Yosemite MAPS team, leaving Kristin and Axel in charge of the banding on Rota. In total, they captured, banded, and released 348 of Rota's resident birds. These are all forest-dwelling, non-migratory species; these birds live their whole lives on this tiny remote island. As we continue to band and recapture these birds, we will learn more about their population trends, their survival, and their reproductive rates - and how these things may be changing over time.

The team made some new additions to our knowledge in how some of the birds on Rota differ from birds of the same species on Saipan, where we have many years of previous data collection. Notably, Rota's sihek (Mariana Kingfishers) have some different plumage details at different ages from Saipan's sihek. On Rota, young sihek have a golden wash to their underwings and the sides of the breast which can be useful in determining that they're in juvenile plumage - something Saipan sihek do not show.

A bander holds a Rota White-eye, or nosa' luta, for a photo as part of scientific documentation. Photo by Kristin Attinger.

The team captured three individual nosa' luta (Rota White-eyes), a species unique to Rota which lives in the canopies of high-altitude forests. While in the long term we hope to capture more so as to understand the demographics of this unique species, these three have already contributed greatly to our understanding through DNA sampling. Each nosa' had some feathers and a tiny drop of blood collected, which will begin to help the local wildlife department study the genetics of these birds, an important step in protecting them against future catastrophe.

A bander holds a Black Drongo for a photo as part of scientific documentation. Photo by Kristin Attinger.

Two adult Black Drongos were also captured, a new species for TMAPS banding in the Marianas! Black Drongo is an introduced species that is most frequently found in villages, grasslands, and farmland on the island so it's rare for them to come into the forests where we band. Their impacts on the native species are not fully understood yet, except that locals often talk about how aggressive they are toward other native landbirds. While we don't expect to capture many of them in our TMAPS nets over the coming years, we'll be carefully documenting each one to improve knowledge on this species - because while they're very common in parts of Asia, their molts have not been thoroughly examined or described.

A micronesian Starling or "sali." Photo by Tony Morris

Another striking difference between Rota data and past seasons on Saipan are just how many sali we caught! Sali (Micronesian Starling) is a native species on the island, and they are well-known for their voracious fruit-eating habits, their crazy yellow eyes, and to our banders, the pain they put us through when they bite and grab while we're trying to work. To you who have met Northern Cardinals and struggled, let me just say, you haven't met sali yet, and you might yearn for cardinals afterward as a refreshing easy bird.

It's not currently known why, but Rota has an incredibly high sali population. Locals I spoke to suggested that the reason is that Rota has so much native forest remaining that it has better food resources for them than the other islands do. Another thing we noticed was that the majority of sali we captured were in definitive basic plumage - full adults, with very few juveniles or immature birds present. I observed adults feeding fledglings in the villages in March, so their nesting season does correspond to our spring banding season, but it's possible that the population is at a sort of carrying capacity where juveniles don't live long because the long-lived adults are already present and consuming most of the available food. Or, perhaps we'll find that the inexperienced juveniles from previous months struggled during Rota's two typhoons in 2023, leaving mostly experienced adults on the island when we arrived, and that future seasons will bring more juveniles into our nets. There could be other things going on - with only one banding season it's hard to know any concrete answers to anything just yet.

All kinds of other little detailed differences came up while banding on Rota that will take additional seasons to understand. This new field season, during the wet season, will bring new challenges and new fun, including Rota's coconut festival in September to celebrate the tree that has enabled cultures across the Pacific Islands to flourish. We can't wait to tell you more in upcoming blog posts!

A hermit crab, or "umang," race during the coconut festival. Video by Lauren Helton.