Part 1: Rota Scouting Trip by Lauren Helton

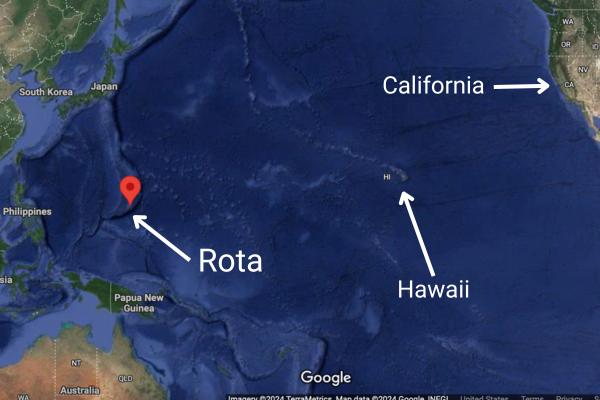

If I were to ask you to point to the island of Rota on a map, would you know where that is?

Google Earth image showing the location of Rota in the western Pacific.

Many people have heard of the famous Mariana Trench, the deepest part of the Earth's ocean floor. But many don't realize that bordering that trench, at a latitude roughly halfway between Japan and Australia, is a chain of volcanic islands including a US territory (Guam) and US commonwealth (Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, or CNMI). Rota is the southernmost island of the CNMI, a tiny island with a rich and varied history spanning thousands of years of human civilization, lush tropical rainforests and coral reefs, and a suite of birds including a unique endemic species found nowhere else in the world, the nosa' luta, or Rota White-eye.

IBP Biologist and Scientific Illustrator Lauren Helton stands in front of a latte stone on the island of Rota.

I'm Lauren, a biologist with IBP's MAPS and TMAPS programs, and I'm working to establish the first TMAPS mist-netting stations on the island of Rota. From 2008-2018, IBP operated a set of six mist-netting stations on the neighboring island of Saipan. Those years of data showed that Saipan's native birds are generally experiencing a slow decline (see: Saipan's birds on a precarious perch.)

A page from Lauren's field sketchbook.

On Saipan, habitat loss and degradation are one of the main threats to those species, but on Rota, the native habitat is more intact; there are fewer people, and there is much less development and land clearing. The CNMI Department of Fish and Wildlife has asked IBP to monitor the population trends of birds on Rota so that they can be compared with birds on Saipan, as the islands share many of the same species and habitat conditions.

In late January, I took my first trip to Rota to scout out the island, meet with local wildlife staff, landowners, and island residents, and get a feel for life there to better prepare for starting this project. Truly, my journey began while still on Guam, where I met with a couple of Rota residents returning home. One asked me, "Have you been to Rota?" and when I said no, not yet, he smiled and gave an approving gesture reminiscent of a chef's kiss. "It's Jurassic Park," he told me. It didn't take long to confirm that he was absolutely right - though the dinosaurs here are much smaller and flighted, but the steep cliffs full of lush forest are everywhere you go.

A stone mortar and pestle on Rota.

I immediately fell in love with the island. Every morning, I woke up to beaches of rugged limestone carved from ancient fossilized reefs, turquoise blue water, uncountable hermit crabs, and some of the kindest, most welcoming people I've ever met. I had to re-train my brain to use the Chamorro names for birds, which are more familiar to most of the people on Rota than the names we use in English. Just like in English, the Chamorro names are often descriptive - sometimes reminiscent of the bird's vocalizations (kakkak and tottot are great examples of this), or sometimes related to behavior (na'abak, "the one who will lead you astray," due to its habit of flitting through the woods at a pace that keeps it just out of the reach of curious children, occasionally resulting in village search parties.)

Latte stones in the ruins of Alaguan Village. The latte stone on left is one of only two in all the islands that remains upright with both pieces (haligi and tasa) in their original position despite a thousand years or more of earthquakes and colonization.

From out of Rota's native limestone rocks and soil spring a diverse community of plants including several endangered and endemic species, and the ancient carved pillars called latte (pronounced like it rhymes with "patty") stones which once held the Chamorros' homes above the ground to prevent flooding in times of torrential rain. I was very generously given a tour of some cultural sites by James Bamba, a Chamorro cultural practitioner, weaver, and also endangered plant expert. Originally from Guam, James has found himself at home on Rota where he weaves pandanus leaves using traditional methods, and helps to grow and distribute Rota's native and endangered plant species for conservation and restoration projects. While exploring the remnants of an ancient village on the north end of the island, with its latte stones, pottery shards, mortars and pestles, and slingstones, we heard and then saw åga, the endangered Mariana Crow. Rota is the last stronghold for their population, which has been reduced greatly across the islands due to a suite of problems including predation by cats and the brown tree snake (on Guam) as well as a mysterious inflammatory disease known as AEX (Aga Eucaryote X). Rota's population of åga is small and closely monitored by a team based out of the University of Washington which is working to understand the disease and its effects on the birds.

James Bamba (left) teaches TMAPS banders Axel and Kristin (more on them in Part 2) how identify Rota's endangered trees.

Our TMAPS project on Rota will primarily focus on passive mist-netting for the forest birds of Rota in order to examine adult survivorship as well as productivity of young, just like in the mainland MAPS program. The project is mainly driven by a need to understand the demographics of the nosa' luta (Rota White-eye) in particular, a species endemic to Rota. In addition to banding and recapturing these birds across six stations on the island, we will collect feather samples and a tiny amount of blood per bird as a DNA sample to allow geneticists to understand how individuals in the population are related, which is important in small, isolated, at-risk populations so that conservation projects that hold birds for potential future breeding programs can have a healthy gene pool in their breeding birds.

A bander holds a nosa' luta or Rota White-eye. Photo by Blake Massey.

But along with nosa', we will also band, measure, photograph, and then release the birds associated with nosa''s forested habitats, both native and non-native. Learning about a suite of species can allow researchers to better predict what kinds of habitats support which kinds of birds, how they relate to each other, and how the bird community as a whole handles challenges such as typhoons, drought, land use changes, and more. Among the species shared between Rota and Saipan are the tottot (Mariana Fruit Dove, official bird of the CNMI), paluman kotbata (White-throated Ground Dove), paluman apu (Philippine Collared Dove, introduced in the ~1700s), sihek (Mariana Kingfisher, though the Rota subspecies is different from the subspecies on Saipan), sali (Micronesian Starling), egigi (Micronesian Myzomela), and na'abak (Micronesian Rufous Fantail), now split from Rufous Fantail as its own unique species.)

A Mariana Fruit Dove preens in an aviary. Photo by Peter Miller

In March, I will be back on Rota, this time with Kristin Attinger and Axel Rutter, two TMAPS bird banders who previously worked at our Fort AP Hill (now Fort Walker) MAPS stations in Virginia. Our first task will be to set up the banding stations we will use on the island, which involves finding sites we can place our arrays of nets for each station, and creating trails between all of them, which we expect will take the full month. It's the dry season on Rota right now, when the underbrush is at its low point, which is a perfect time to find paths and flight corridors and places we can set up our nets - but "dry" is never fully dry in this environment, and the greenery is always thick and fast-growing and ready to close back in on our net lanes, so it won't be an easy job!

Part 2: Setup and Project Start: March 2024 by Lauren Helton

After a few days on Saipan to purchase supplies that wouldn't be present on Rota, I picked up this year's TMAPS crew, Kristin Attinger and Axel Rutter, at the airport. They got a day to recuperate from the marathon flights that had taken them from the eastern and Midwest US all the way to Japan and then down to the CNMI, and then we packed up all our field gear, sent it as cargo to Rota, and then hopped on that tiny 7-passenger airplane for the half-hour trip to our new home.

TMAPS banders Kristin Attinger and Axel Rutter in front of one of the largest latte capstones in the Marianas.

It took us all of March to set up the banding stations which will be used for the duration of the TMAPS project on Rota. The six stations span across the whole island, from east to west and from sea level to a lush mountainside. Each station has twenty net lanes - ten are run one month, the other ten the subsequent month. And boy, cutting net lanes in pristine native forest is not easy! Native hardwoods on Rota are hard woods, not easily cut through, plus the canopy is often fairly low, with lots of head-level branches that need to be trimmed so we can make way for nets. One of the most common plants in our sites, Triphasia trifolia (sweetlime, among other names)

Kristin threads the needle, setting up a net lane between Triphasia and other trees. Mist net setup on Rota is incredibly difficult - it can be rare to find good open corridors for nets already available.

A "boonie bee" or Polistes stigma. Photo by Gerard Chartier.

If the plants themselves weren't tricky enough, underfoot is the constant rough limestone made of Rota's ancient uplifted coral reef, which shreds shoes that aren't extra-durable. And tucked away in those plants are "boonie bees" as they are locally known, the tropical paper wasp Polistes stigma, which nests under leaves we frequently had to trim to make room for our net lanes and which is extremely, aggressively territorial and makes ample use of its stinger to get you to leave.

But on days off, we had Rota's beautiful white sand and limestone beaches and reefs for snorkeling and exploring, local friends, and so much good food. Kristin and Axel learned how to spot wild edible citrus, find sea salt on exposed cliffs, select and harvest coconuts, and navigate grocery stores mostly filled with products labeled in Korean, as South Korea is close to Rota and is one of the major sources of imported goods. The habitats we band in are also full of other kinds of treasures - historic and prehistoric artifacts spanning back thousands of years of civilization, endangered plants, deer and monitor lizards and fruit bats, and a constant, endless natural beauty.

DeBorja Beach on Rota

Axel and Kristin check out a Japanese-constructed WWII tunnel for soldiers to stash gear and hide in on the upland hills of Rota.

After a month of hard work, with all the scratches, wasp stings and exhaustion to prove it, we finally got to band our first day! And for me, it was my last full day on Rota - one opportunity to make sure everything would run smoothly after my departure, and of course, one chance for me to see firsthand some of the things that are different on Rota compared to all of my past work on Saipan. We began by banding at a site called Chugai (pronounced “tsugai”), which is tucked into the edge of native limestone forest along a grassy savannah that was once home to a prehistoric village called Gampapa, and which hosts a cave full of pictographs of fruit bats, turtles, and more.

Not long after opening our mist-nets, we captured our first birds on Rota! Na’abak (Micronesian Rufous Fantail), egigi (Micronesian Myzomela), and sihek (Mariana Kingfisher) all found their way to the banding table within those first few hours. All three of these species are endemic to the region, are relatively common on Rota, and are such a treat to get to examine up close.

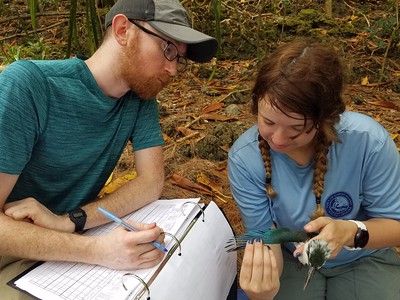

Axel and Kristin process and record data about their first Mariana Kingfisher, captured at Chugai.

Na’abak on these islands were recently split from Rufous Fantail as their own species due to their distinct genetics. They are some of the most numerous birds in the Marianas, and yet for us bird banders, their molts are some of the most puzzling - for some individuals may follow the typical sequence of primary replacement in one year, only to swap to an unusual bidirectional replacement sequence starting in the middle of the primaries the next. One of the first na’abak we captured also had signs of eccentric primary replacement that was suspended, so that only the outer half of the primaries had been molted. With a lack of a need to migrate or any particularly strong seasonal changes, these birds may have adopted molt strategies that suit their lives in ways we’re not used to examining in the temperate zones, and which we are still trying to understand.

A na'abak or Micronesian Rufous Fantail.

Rota egigi, like those on Saipan, usually replace feathers in the typical molt sequence, but they may take 8-10 months to do so. Their wings are in a constant state of molt cline, a gradual change in the age of each feather that shows a gradient of brown (old feathers) to black (new feathers) along the wing. Learning to identify these clines and tell them apart from true molt limits is usually one of the first challenges that banders from the US who come to these islands have to deal with. These are striking birds regardless of young or old, male or female, with their mix of red and black feathers and their long curved nectar-drinking bills.

The Rota subspecies of sihek is unique in the Marianas, with a lot of shimmering turquoise feathers on the crown, whereas on Saipan they have heads that are mostly white, with just a turquoise eyestripe. Males have a shockingly vibrant blue back, while females tend to have a slightly subtler greenish tint to their back and wings which makes them look like their feathers are made of the tropical waters that surround their island homes. Their proportions look ridiculous, with huge bills and heads and tiny feet, almost like someone took parts of two birds of vastly different sizes and glued them together.

An egigi or Micronesian Myzomela.

We wound up catching six na’abak, one egigi, and one sihek on that first day of banding. While that isn’t a lot, they represent the first eight of many, and a start to exploring the differences in population dynamics and demographics of these species on Rota, where this work has never been done before. Additionally, they will help us understand molt patterns in the tropics among these and related species, and ultimately be participants in conservation efforts for the birds of these remote islands which are faced with all kinds of threats. Stay tuned for our next update from Kristin and Axel, who are out there banding until the end of May and will have lots to tell you about what they’ve learned after a full field season on Rota!

All photos in this blog post taken by Lauren Helton unless otherwise noted.