Once upon a time Willow Flycatchers were a dime a dozen in California’s shrubby riparian habitats, especially wet montane meadows full of–you guessed it–willows. But loss and degradation of these meadows has contributed to the steep decline of this species which was declared endangered in the state of California in 1991. In the early 2000’s, state and federal agencies began ambitious hydrologic restoration efforts in meadows in the Sierra Nevada to help conserve this important habitat and the species that rely on it. But has meadow restoration benefitted Willow Flycatchers?

A new study by IBP scientists and a colleague from the Truckee River Watershed Council looked at how Willow Flycatchers responded to restoration of wet montane meadows. The study used 23 years of Willow Flycatcher survey data- from 1997 through 2019- at 11 montane meadows in and around the Little Truckee Watershed in California, two of which were hydrologically restored during the study period.

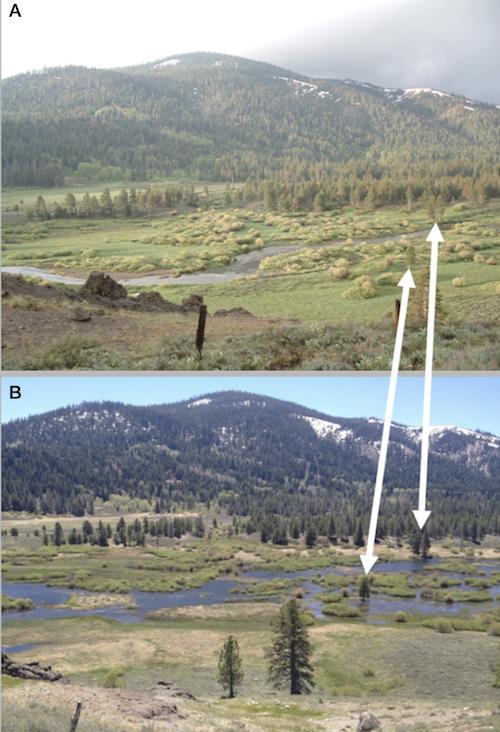

Middle Perazzo meadow one year prior to restoration (top, A) and 8 years after restoration (bottom, B.) White lines indicate reference trees visible in both photos. after restoration, note the more extensive flows over the streambanks during peak runoff. Photo from Loffland et al., 2022

What makes these wet montane meadows so special? Their lush vegetation, abundant insects, and water attract wildlife and are a hotspot for bird diversity. But these same features (except for the abundant insects perhaps) attract humans to meadows too. Human impacts to Sierra meadows over the past 150 years include grazing, dams and water diversions, nearby mining and logging, and road construction. These activities, in combination with drought fueled by climate change, have dramatically altered most meadows.

The once braided, multi-channeled streams that flowed through the meadows became incised, single channels that rarely flooded. As a result, water tables dropped, older willows died off and new ones couldn’t germinate and replace them. Non-riparian vegetation, like sagebrush and conifers, started creeping in, altering the vegetation structure. As the meadows dried, populations of flying insects with aquatic life stages (like damselflies, mayflies and midges) which are important prey for the flycatchers decreased. These changes made the meadows less suitable habitat for breeding Willow Flycatchers.

Restoring the hydrology, or patterns of water flow, in a meadow can help restore the vegetation structure and other important ecological attributes. The restored meadows in this study were restored using the “pond and plug” treatment: Upper Perazzo Meadow was treated in 2009 and Middle Perrazo Meadow was treated in 2010. This treatment involves excavating a portion of the stream channel and using the excavated material to create a semi-permeable “plug” in the channel. This slows down water flow and forces water out over the streambanks which mimics a braided stream and increases soil moisture. The excavated portion of the stream channel forms a “pond” which can also help slow down and spread out stream flow. With this improved hydrology, new willow shrubs can establish and insect populations increase.

In this study, the researchers found that Willow Flycatcher populations declined in 8 out of 9 unrestored meadows while flycatcher populations remained steady in the two restored meadows. While this may not be the “if you build it, they will come” Hollywood ending one might hope for, it is significant.

First, this study provides evidence that the disturbance caused by the pond and plug restoration action itself did not cause Willow Flycatchers to abandon the restored meadows. Second, IBP biologist and lead author of the study Helen Loffland notes that habitat quality at restored meadows did improve:

"Meadow restoration does improve multiple aspects of the habitat that are important for Willow Flycatchers’ breeding season success. Expanding riparian shrub cover results in increased nest cover and protection from predators, weather, and temperature extremes. Rewetting and flooding meadows creates greater extent and heterogeneity of habitat for flying insects which are important prey for these birds. Wetter meadows also provide abundant prey later into the summer when fledglings (and adults) most need it to prepare for migration. Flooded meadows also appear to reduce mammalian predation of nests, especially for edge predators that can easily access nesting areas when meadows are dry.”

But Loffland cautions that meadow restoration is clearly not a magic bullet solution for conserving this species. She notes that Willow Flycatchers use wetlands like montane meadows for all stages of their life, not just breeding. The wetlands they use as stop over sites during migration and those on their wintering grounds in Central and South America are also being degraded or lost to development. Loffland also suggests montane meadow restoration may have had a more significant impact if it had been done 20 years ago, when the region’s population of Willow Flycatchers was larger and better able to expand into restored sites. Once a population gets too small, it is harder for it to recover and recolonize improved habitat. (For instance, IBP research suggests that hearing other Willow Flycatchers singing in a meadow may encourage prospecting Willow Flycatchers to settle there.) She notes that some restored sites which are not close to active breeding sites (and were not in the study area), have not been recolonized by Willow Flycatchers.

IBP biologist and study co-author Lynn Schofield summed up the take home message of the study nicely:

“This study demonstrates that habitat restoration efforts, like pond and plug, have a quantifiable positive effect on the species reliant on those habitats. However, we saw that although the ongoing loss of Willow Flycatchers was greatly slowed or even stopped at restored meadows relative to unrestored habitat, the intervention did not result in flycatcher numbers returning to their historic levels. This indicates that, at least in the time scale of our study, restoration efforts are not able to reverse damage that has already been done, they are only able to prevent further losses. To me, I think the take away is that habitat restoration can be highly beneficial, something that (when needed) should be done as early as is feasible, but it's not a replacement for maintaining healthy habitats in the first place.”