**This post originally appears on the American Ornithological Society's blog Wing Beat**

Back in the summer of 1977, Dr. David DeSante, then an assistant professor at Reed College, took a group of students to work at the Harvey Monroe Hall Research Natural Area, which covers more than 1,500 hectares of alpine habitat, subalpine forest, and meadows on the eastern border of Yosemite National Park. DeSante had long wanted to initiate a long-term bird study and had recently gained access to the site, which was previously used for the Carnegie Institution of Washington’s famous genotype-environment experiments in plant biology. The Harvey Monroe Hall Research Natural Area had a small cabin for cooking and an old garage that had been converted into a rustic bunkhouse. What it lacked in electricity and plumbing, it made up for with incredible scenery.

Slate Creek Valley in the Harvey Monroe Hall Research Natural Area today. Photo courtesy of Bob Wilkerson.

“At first, I didn't know exactly what we were going to do there,” says DeSante. But climate change was on his mind. “There was enough information about it even then; that it was happening and was serious.” DeSante and his students established grids across a 100-hectare subalpine site and, by the end of the summer, realized that they could map the territories of all bird species breeding on the site and determine their breeding productivity. They also recorded climate variables such as snowmelt timing. DeSante would return year after year with students and volunteers; a 32-year subalpine bird and climate study was born.

In “Climate variation drives dynamics and productivity of a subalpine breeding bird community,” DeSante and co-author Jim Saracco of The Institute for Bird Populations present some of the results of this long-term study, which ran from 1978 to 2009. They found that climate variables varied widely over the course of the study. Spring and summer temperatures tended to increase and snowpack melted earlier as the study went on, while summer precipitation decreased.

During years with earlier snowmelt and warmer springs, greater species richness, greater numbers of breeding territories, and earlier fledging dates were recorded, but fewer fledglings were produced per breeding territory. Three species showed strong evidence of a population trend: populations of Clark’s Nutcrackers (Nucifraga columbiana) and Chipping Sparrows (Spizella passerina) declined, while populations of Yellow-rumped Warblers (Setophaga coronata) increased. DeSante and Saracco discuss the complex interactions between climate and avian ecology that may explain these results.

This study provides a rare, multi-decade view of the complex effects of rapid climate change on a high-elevation bird community. It would not have been possible without the collection of fundamental natural history data and the commitment needed to collect these data year after year. Saracco, who analyzed the data but was not involved in the fieldwork, explains:

“I don’t know of any other data sets with detailed maps of multi-species bird territories for 3-plus decades. It is really a remarkable achievement, requiring real dedication from Dave and all those that helped with this work over the years. The data set is especially important in the context of understanding ecological consequences of climate change, which is happening relatively rapidly in many higher elevation ecosystems, such as the Sierra Nevada.”

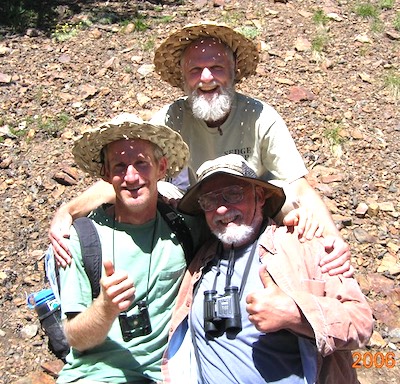

Dr. David DeSante with former field assistants Elliot Burch and Brett Engstrom in 2006, near the end of the study. Photo courtesy of Dr. David DeSante.

For DeSante, the study was a labor of love. “What was so amazing is just how beautiful the subalpine, tree-line habitat is in the Sierra Nevada range,” he says, “and the opportunity to live up there where we were working—the place is so magical. What a gift to be able to live that way with a bunch of like-minded people, having a focus and living close to the earth. Oh man, what a lucky life!”

Data collection at the study site ended in 2009. “By then I was almost 70,” explains DeSante, “I was beginning to lose my hearing and it was getting hard to run around those mountains at 10,000 or 11,000 feet.” But he has hopes that someday the study will restart. Certainly, the Harvey Monroe Hall Research Natural Area—where human disturbance other than climate change is minimal and studies like this one provide a historical record—offers a rare opportunity to examine the effects of recent extreme climatic events, like multi-year droughts, which are likely to become more frequent in the future.