On June 19th, banders at the Apache Springs MAPS station in Bandelier National Monument near Sante Fe, New Mexico, caught a very unusual bird–an albino Chipping Sparrow! The "one in a million" sparrow was aged as a "hatch year" bird, meaning it hatched this spring.

Okay, technically it's not "one in a million" as the incidence of albinism in birds is thought to be about 1 in every 1,800 birds, says Bandelier's lead bander Keegan Tranquillo. While the mechanism of albinism is understood, there actually isn't much recent research on its frequency. Still catching this standout sparrow was quite a thrill.

All-white birds are more commonly leucistic rather than albino. Albinism is the genetic inability to produce pigments, while leucism is only a partial loss of pigmentation and leucistic animals typically have a pigmented, rather than pink, iris as well as other pigmented body parts. Albinism is easier to define in humans and most mammals because we can only produce one pigment, melanin. But birds (as a group) can produce multiple pigments: melanin, carotenoids, and porphyrins. In addition, some feather colors- for example most blues and iridescent colors- result from "structural pigments." So birds have to lose the ability of producing multiple different pigments depending on how many pigments are typically produced by the species. And there is some disagreement as to whether albino is an absence of melanin specifically or pigments generally. (If you are interested in coloration in birds, which is fascinating, this article gives a more detailed explanation.)

Brand new, unworn wing feathers are one of the characteristics Tranquillo used to age this bird as a "hatch year." Photo by Keegan Tranquillo.

Distinguishing albino from leucistic birds can be tricky unless you can get a good look at the eye, either via a great photo or having a bird in the hand. This Chipping Sparrow was definitely a albino as Tranquillo and his fellow banders documented that the bird had a pink iris and no pigment in its bill, legs or toenails; so the loss of pigmentation wasn't confined to the feathers.

You might wonder, how do you identify or age a bird that lacks pigmentation? So many of the cues we use to identify species, or determine how old a bird is, are based on color. "I hate to say I just knew it was a chipper, but I just did," says Tranquillo. His experience handling birds, familiarity with their size and shapes, plus his knowledge of the species typically present at the Apache Springs station gave him a good sense of the "jizz" of a Chipping Sparrow even in the absence of color. Subsequent measurements would confirm his identification. This individual's fluffy body feathers, brand new flight feathers, and remnants of its nestling yellow gape, made it obvious that it was a hatch year bird.

And if there was any doubt, the bird's behavior when it was released quickly erased it. The albino sparrow quickly rejoined a family group of Chipping Sparrows and was observed begging and being fed by the adults.

A typical hatch year Chipping Sparrow. Note the remnants of a yellow gape typical of a nestling bird. Photo courtesy of Keegan Tranquillo.

But this is not the first time an all-white juvenile Chipping Sparrow has been observed at this station! "Interestingly enough, there was another all white juvenile chipping sparrow we spotted at this same location in 2018," says Tranquillo. "We never caught it to confirm if it was albino or not, but after this one I suspect it may have been. We must have a parent carrying the genetics near the station," he adds."

Sadly, being albino puts this young sparrow at a disadvantage. Just as this bird stands out to birders, it also stands out to predators. The streaky brown plumage of a typical juvenile Chipping Sparrow provides good camouflage. Unless there's a layer of snow on the ground, this bird will stick out like a sore thumb to predators like Sharp-shinned Hawks and bobcats.

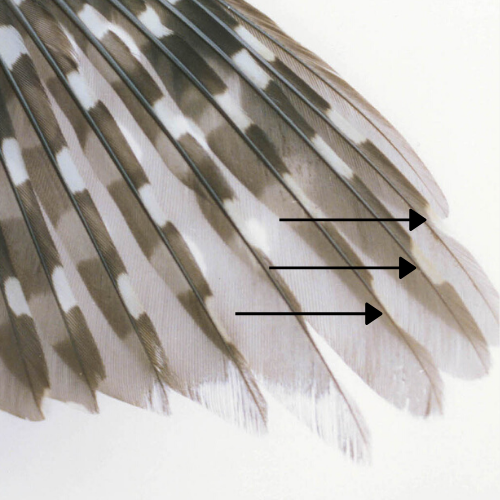

And white feathers are not just poor camouflage, they are also weaker. Melanin pigment actually makes feathers stronger and more resistant to wear and tear. That's why many mostly white or pale birds, i.e. many terns, have black wing feathers or wing tips. "White feathers definitely don't have the same strength as darker feathers and wear much more quickly," says IBP's MAPS coordinator Dani Kaschube. "For example white spots on woodpecker wings can wear completely away during the life of the feather and by the time feather is molted it doesn't have white spots any longer, just holes where the white use to be." This young sparrow's white feathers will likely wear out faster than normal. "That excess feather wear will cause the bird to be less aerodynamic and be less efficient at thermoregulation," says Kaschube.

The white spots on this woodpecker's primaries have worn away on the leading edge the feathers leaving divots. Photo from: Froehlich, D. 2003. Ageing North American landbirds by molt limits and plumage criteria: a photographic companion guide to the Identification Guide to North American Birds, Part I. Slate Creek Press, Bolinas, CA.

Tranquillo agrees that the decks are stacked against this albino sparrow. He notes that the all-white juvenile Chipping Sparrow observed (but not caught) at the station in 2018 was seen twice. "We saw the one from 2018 in the station for another banding period after the initial observation. So that one survived at least a week." He adds "I should go look for this current one to get some information on its survival."

Best of luck to this little bird. Perhaps it will beat another set of steep odds and be recaptured in the future so we can get more information about the survival of albino birds. And thanks to Keegan Tranquillo for sharing this cool story with us! Keegan has been part of the MAPS community since 2010 and has run the MAPS bird monitoring protocol for IBP, and other institutions, all over the country–even American Samoa!