In 2018 and 2019, the California Coast saw a surge of vagrant Masked and Nazca boobies. The two species, which were split by the American Ornithologists Union in 2000, are typically distinguished by the color of the base of the bill. Nazca Boobies' bills are pinkish orange to orange at the base and Masked Boobies' bills are greenish yellow to yellow at the base. But in younger boobies, bill color isn't fully developed, so how do you distinguish the species?

In a new paper published in the journal Western Birds, IBP biologist Peter Pyle used digital photos from the California Birds Record Committee to identify the progress of the first primary molt in Masked and Nazca Boobies - so as to accurately age photographed birds. Boobies, like most birds, replace primaries from the innermost (p1) to the outermost (p10) feather, and past work (in 1962!) established a time scale for the dropping of each primary, from 6-7 months of age for p1 to 20-22 months of age for p10. Aging the birds by which primary is being molted allowed Pyle to, in turn, document the progress of bill color change and plumage change in younger birds, and suggest better criteria for distinguishing the two species according to age (i.e., primary molt progress).

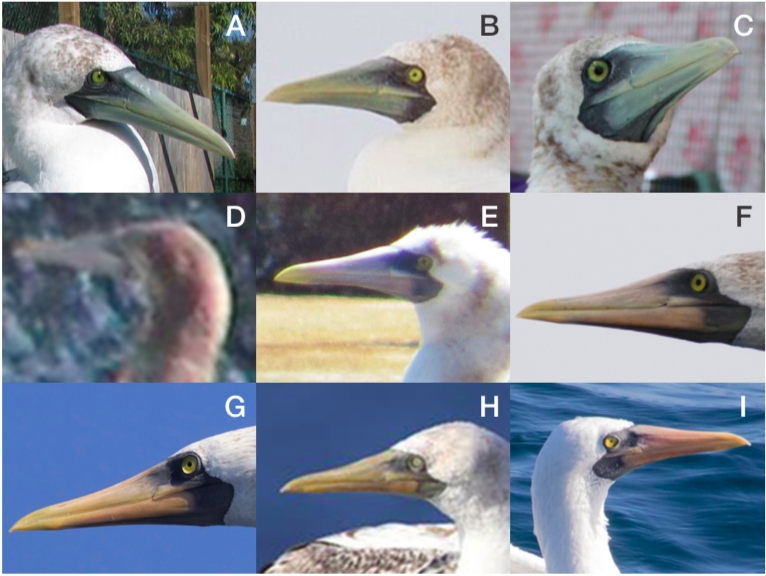

A figure from the paper in Western Birds shows the progression of bill colors in provisionally identified Masked (A–C) and Nazca (D–I) boobies through their first primary molt. Photo credits to A. Kannan, C. Taylor, T. Gussler, J. Scholes, B. O’Connor, N. Desnoyers, M. Force, J. Feenstra, M. Senac.

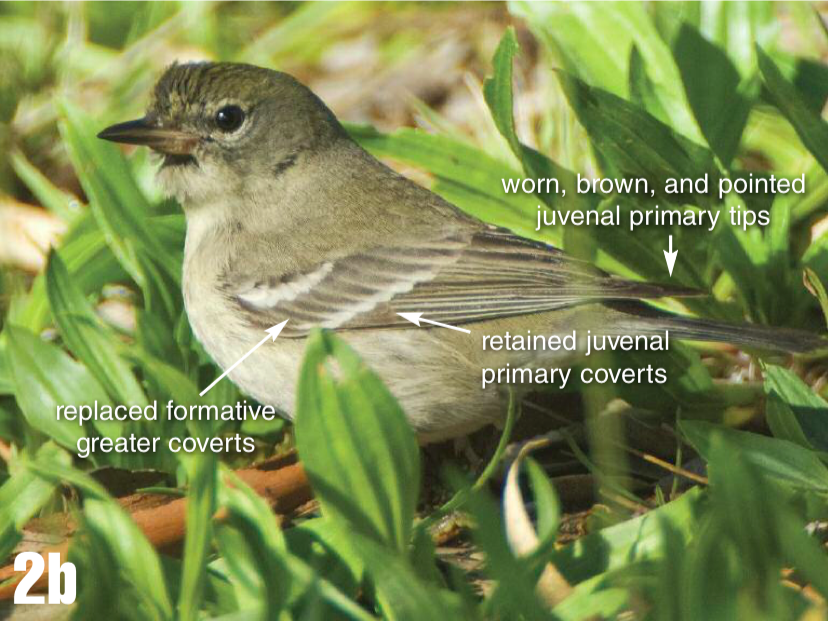

Pyle helped pioneer the use of photography to age birds by examining molt and the age of feathers in photos, an activity he calls "birding by feather." In 2008, Pyle wrote a great article on how to bird by feather that you can read here: Birding by Feather: A Molt Primer. Digital photography helped make detailed examinations of wild birds accessible; not all birds have to be captured and scrutinized in hand. Digital images are easily shared and improvements in the quality of digital photography have led to crisp, detailed images that allow feather-by-feather analysis and contain a wealth of information about the pictured bird–if you know what to look for.

A photo from "Birding by Feather: A Molt Primer" shows the clues in the photo that show that this Pine Warbler is a yearling.

With COVID-19 at large, it is better for public health (as well as reducing carbon emissions) if we focus on birding in our home areas. If you can't build your life list by seeking birds afar, you can challenge yourself, and get to know your local birds more intimately by photographing them, learning the current molt terminology and ageing techniques, and trying your hand at birding by feather.

Those of you who live on the California Coast, just might find a vagrant booby in your local birding patches. Some suspect that more of these seabirds have been straying to California recently due to global ocean warming related to climate change and/or an increased occurrence of El Niño–Southern Oscillation weather patterns. A happier hypothesis proposes that the increased numbers of vagrants in 2018 and 2019 might be due to an especially productive breeding season off Mexico and on the Galapagos Islands in 2017.

If you have a young booby in your sights, Pyle says that the species can still be distinguished by bill color, though the differences are more subtle: "Masked Boobies have bluish-green bill bases with greenish yellow tips, and these colors appear to be relatively consistent while becoming brighter with age, from juvenile to definitive plumage. Nazca Boobies, by contrast, from juveniles through the first wave of primary molt, have duskier bill bases that are mixed with horn color (medium-pale brownish, often tinged mustard or olive) at younger ages and bill tips that are a brighter yellow and usually tinged orangish or golden." These color differences, especially the brighter golden-yellow tips of young Nazca Boobies, can help confirm identification even in distant or blurry photographs.

Next time you go birding take pictures if you can and share them! You can submit them to media catalogs like eBird (Cornell Lab of Ornithology's Macauley Library). Your images can help scientists and birders learn more about the molts, plumages and other features of a bird, which can help determine its age, sex, species and subspecies.

In 2008 and primarily in response to global warming and rising gas prices, Pyle wrote "Dare I predict that 'digital birding' at home on our computer monitors, to fully classify and document select observations, will someday supplant long-distance travel to simply log sight records at the species level?" Today, in the COVID-era, this seems quite prescient.