How many species of White-breasted Nuthatch are there? Genetic studies suggest at least three in the U.S., and maybe four. Vocalizations, which show remarkable differences among subspecies, strongly suggest three. While some field guides have noted these differences, they had not been well-characterized until Nathan Pieplow and I published our work on this in 2015.

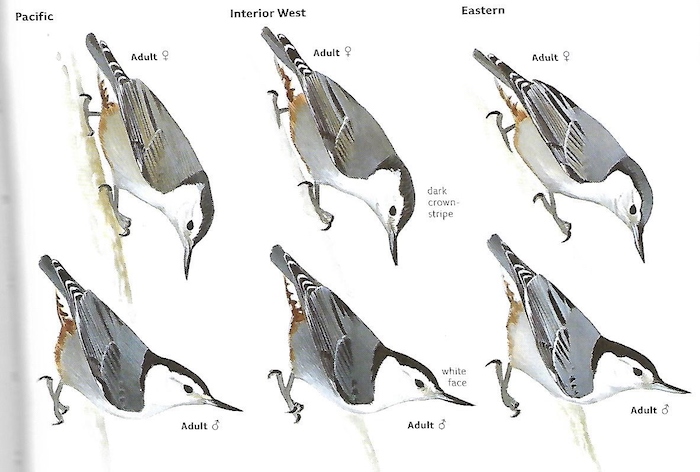

If these subspecies ARE elevated to full species status, telling them apart visually is going to be a real challenge as one can see from the illustration below from the Sibley Guide to Birds (2nd edition).

From the Sibley Guide to Birds, 2nd Edition

Luckily, these three forms can be reliably distinguished by songs and calls. All three give a song that is a series of nasal, over-slurred notes, but the pitch of these notes differs among them, increasing from east to west. Thus, the eastern subspecies (Sitta carolinensis carolinensis) song is lowest in pitch and the Pacific (S. c. aculeata) highest.

SONGS

Eastern subspecies song recorded by Nathan Pieplow in Platte County, NE:

Recorded by Nathan Pieplow in Platte County, NE. Produced by Ed Pandolfino.

The Pacific subspecies (S. c. aculeata; recorded by me in Tehama County, CA) song is much higher:

Recorded by Nathan Pieplow in Platte County, NE. Produced by Ed Pandolfino.

Songs of the two subspecies in the interior west group (S. c. nelsoni and tenuissima) are intermediate in pitch.

Note, however, that Pacific (S. c. aculeata) much more often give a “tooey” song (my recording from Sacramento County, CA), quite unlike the songs of the other White-breasted Nuthatches:

Recorded (Sacramento County, CA) and produced by Ed Pandolfino.

CALLS

These three forms are also easily ID’d by their most common calls. Both the eastern and Pacific birds give a very nasal, highly modulated (varying rapidly in pitch) calls which appear similar spectrographically. However, the calls of the eastern birds are much lower in pitch, with no overlap in pitch between these subspecies. Listen to the examples below:

Eastern call recorded by Nathan in Manistee County, MI:

Recorded by Nathan Pieplow in Manistee County, MI. Produced by Ed Pandolfino.

Pacific call from my recording in Placer County, CA:

Recorded (Placer County, CA) and produced by Ed Pandolfino.

The two interior west subspecies most often use one or two call types (shown below), and these sound nothing like the calls of eastern or Pacific nuthatches:

The "pitter" call recorded by Nathan in Mesa County, CO (S. c. nelsoni):

Recorded by Nathan Pieplow in Mesa County, CO. Produced by Ed Pandolfino.

The “trill” call recorded by me in Union County, OR (S. c. tenuissima):

Recorded (Union County, OR ) and produced by Ed Pandolfino.

Both interior subspecies may give either call type and there is no consistent difference between these calls from these two subspecies.

PRACTICAL APPLICATION OF THESE VOCAL DIFFERENCES

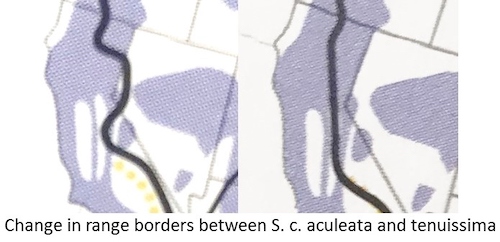

Ever since Grinnell and Miller published their landmark book The Distribution of the Birds of California in 1944, there has been confusion about the ranges of the Pacific White-breasted Nuthatches and the interior subspecies, S. c. tenuissima. The problem arose from misidentification of some birds from northeastern California which led Grinnell and Miller to show erroneous range maps of these subspecies.

Using the vocal distinctions described above, a group of us were able to clarify and correct the actual ranges of these taxa. Below is a comparison of the range maps from the 6th (on the left) and 7th (on the right) editions of the National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America showing the corrected ranges.

From National Geographic's Field Guide to Birds

In general, we humans rely on our vision more than our other senses. And so while many birders listen to vocalizations to help them find birds, in most cases we rely on visual information like shape and plumage characteristics to identify them. But for birders interested in distinguishing between sub-species of the White-breasted Nuthatch, the ear is likely a better tool than the binoculars.

Ed Pandolfino is a member of IBP's Board. He earned a Ph.D. in Biochemistry from Washington State University. After twenty years working in various management positions in the medical device industry, he retired in 1999 and has since devoted his time to ornithology. Ed has served as president of Western Field Ornithologists, vice-president of San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory, conservation chair for Sierra Foothills Audubon Society, and Regional Editor for Northern California for North American Birds. He has published more than three dozen articles on status, distribution, behavior of western birds. He co-authored with Ted Beedy, Birds of the Sierra Nevada: Their Natural History, Status, and Distribution published by U.C. Press in May 2013. He has conducted ornithological field research and consulted for the US Forest Service, The Nature Conservancy, Point Blue, Sacramento Valley Conservancy, and Williams Wildland Consulting.

.jpg)